Sisyphus

In Greek mythology, Sisyphus or Sisyphos (/ˈsɪsɪfəs/; Ancient Greek: Σίσυφος Sísyphos) was the founder and king of Ephyra (now known as Corinth). He was a devious tyrant who killed visitors to show off his power. This violation of the sacred hospitality tradition greatly angered the gods. They punished him for trickery of others, including his cheating death twice. The gods forced him to roll an immense boulder up a hill only for it to roll back down every time it neared the top, repeating this action for eternity. Through the classical influence on modern culture, tasks that are both laborious and futile are therefore described as Sisyphean (/sɪsɪˈfiːən/).[2]

Etymology

R. S. P. Beekes has suggested a pre-Greek origin and a connection with the root of the word sophos (σοφός, "wise").[3] German mythographer Otto Gruppe thought that the name derived from sisys (σίσυς, "a goat's skin"), in reference to a rain-charm in which goats' skins were used.[4]

Family

Sisyphus was formerly a Thessalian prince as the son of King Aeolus of Aeolia and Enarete, daughter of Deimachus.[5] He was the brother of Athamas, Salmoneus, Cretheus, Perieres, Deioneus, Magnes, Calyce, Canace, Alcyone, Pisidice and Perimede.

Sisyphus married the Pleiad Merope by whom he became the father of Ornytion (Porphyrion[6]), Glaucus, Thersander and Almus.[7] He was the grandfather of Bellerophon through Glaucus;[8][9] and of Minyas, founder of Orchomenus, through Almus.[10] Another account related that Minyas was Sisyphus's son instead.[11]

In other versions of the myth, Sisyphus was the true father of Odysseus by Anticleia instead of Laërtes.[12]

Mythology

| Greek underworld |

|---|

| Residents |

| Geography |

| Prisoners |

| Visitors |

Reign

Sisyphus was the founder and first king of Ephyra (supposedly the original name of Corinth).[8] King Sisyphus promoted navigation and commerce but was avaricious and deceitful. He killed guests and travelers in his palace, a violation of guest-obligations, which fell under Zeus' domain, thus angering the god. Sisyphus took pleasure in these killings because they allowed him to maintain his iron-fisted rule.

Conflict with Salmoneus

Sisyphus and his brother Salmoneus were known to hate each other, and Sisyphus consulted the Oracle of Delphi on just how to kill Salmoneus without incurring any severe consequences for himself. From Homer onward, Sisyphus was famed as the craftiest of men. He seduced Salmoneus's daughter Tyro in one of his plots to kill Salmoneus, only for Tyro to slay their children when she discovered that Sisyphus was planning on using them to eventually dethrone her father.

Cheating death

Sisyphus betrayed one of Zeus's secrets by revealing the whereabouts of the Asopid Aegina to her father, the river god Asopus, in return for causing a spring to flow on the Corinthian acropolis.[8]

Zeus ordered Thanatos to chain Sisyphus in Tartarus. Sisyphus was curious as to why Charon, whose job it was to guide souls to the underworld, had not appeared on this occasion. Sisyphus slyly asked Thanatos to demonstrate how the chains worked. As Thanatos was granting him his wish, Sisyphus seized the opportunity and trapped Thanatos in the chains instead. Once Thanatos was bound by the strong chains, no one died on Earth, causing an uproar. Ares, the god of war, became annoyed that his battles had lost their fun because his opponents would not die. The exasperated Ares intervened, freeing Thanatos, enabling deaths to happen again and turned Sisyphus over to him.[13]

In some versions, Hades was sent to chain Sisyphus and was chained himself. As long as Hades was trapped, nobody could die. Consequently, sacrifices could not be made to the gods, and those that were old and sick were suffering. The gods finally threatened to make life so miserable for Sisyphus that he would wish he were dead. He then had no choice but to release Hades.[14]

Before Sisyphus died, he had told his wife to throw his naked corpse into the middle of the public square (purportedly as a test of his wife's love for him). This caused Sisyphus to end up on the shores of the river Styx when he was brought to the underworld. Complaining to Persephone that this was a sign of his wife's disrespect for him, Sisyphus persuaded her to allow him to return to the upper world. Once back in Ephyra, the spirit of Sisyphus scolded his wife for not burying his body and giving it a proper funeral as a loving wife should. When Sisyphus refused to return to the underworld, he was forcibly dragged back there by Hermes.[15][16]

In another version of the myth, Persephone was tricked by Sisyphus that he had been conducted to Tartarus by mistake, and so she ordered that he be released.[17]

In Philoctetes by Sophocles, there is a reference to the father of Odysseus (rumoured to have been Sisyphus, and not Laërtes, whom we know as the father in the Odyssey) upon having returned from the dead.[clarification needed] Euripides, in Cyclops, also identified Sisyphus as Odysseus's father.

Punishment in the underworld

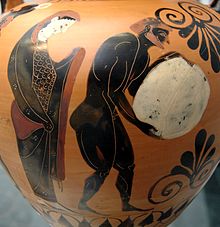

As a punishment for his crimes, Hades made Sisyphus roll a huge boulder endlessly up a steep hill in Tartarus.[8][18][19] The maddening nature of the punishment was reserved for Sisyphus due to his hubristic belief that his cleverness surpassed that of Zeus himself. Hades accordingly displayed his own cleverness by enchanting the boulder into rolling away from Sisyphus before he reached the top which ended up consigning Sisyphus to an eternity of useless efforts and unending frustration. Thus, pointless or interminable activities are sometimes described as "Sisyphean". Sisyphus was a common subject for ancient writers and was depicted by the painter Polygnotus on the walls of the Lesche at Delphi.[20]

Interpretations

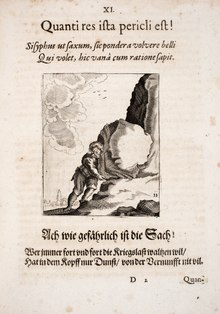

According to the solar theory, King Sisyphus is the disk of the sun that rises every day in the east and then sinks into the west.[21] Other scholars regard him as a personification of waves rising and falling, or of the treacherous sea.[21] The 1st-century BC Epicurean philosopher Lucretius interprets the myth of Sisyphus as personifying politicians aspiring for political office who are constantly defeated, with the quest for power, in itself an "empty thing", being likened to rolling the boulder up the hill.[22] Friedrich Welcker suggested that he symbolises the vain struggle of man in the pursuit of knowledge, and Salomon Reinach[23] that his punishment is based on a picture in which Sisyphus was represented rolling a huge stone Acrocorinthus, symbolic of the labour and skill involved in the building of the Sisypheum. Albert Camus, in his 1942 essay The Myth of Sisyphus, saw Sisyphus as personifying the absurdity of human life, but Camus concludes "one must imagine Sisyphus happy" as "The struggle itself towards the heights is enough to fill a man's heart." More recently, J. Nigro Sansonese,[24] building on the work of Georges Dumézil, speculates that the origin of the name "Sisyphus" is onomatopoetic of the continual back-and-forth, susurrant sound ("siss phuss") made by the breath in the nasal passages, situating the mythology of Sisyphus in a far larger context of archaic (see Proto-Indo-European religion) trance-inducing techniques related to breath control. The repetitive inhalation–exhalation cycle is described esoterically in the myth as an up–down motion of Sisyphus and his boulder on a hill.

In experiments that test how workers respond when the meaning of their task is diminished, the test condition is referred to as the Sisyphusian condition. The two main conclusions of the experiment are that people work harder when their work seems more meaningful, and that people underestimate the relationship between meaning and motivation.[25]

Literary interpretations

- Homer describes Sisyphus in both Book VI of the Iliad and Book XI of the Odyssey.[9][19]

- Ovid, the Roman poet, makes reference to Sisyphus in the story of Orpheus and Eurydice. When Orpheus descends and confronts Hades and Persephone, he sings a song so that they will grant his wish to bring Eurydice back from the dead. After this song is sung, Ovid shows how moving it was by noting that Sisyphus, emotionally affected for just a moment, stops his eternal task and sits on his rock, the Latin wording being inque tuo sedisti, Sisyphe, saxo ("and you sat, Sisyphus, on your rock").[26]

- In Plato's Apology, Socrates looks forward to the after-life where he can meet figures such as Sisyphus, who think themselves wise, so that he can question them and find who is wise and who "thinks he is when he is not."[27]

- Albert Camus, the French absurdist, wrote an essay entitled The Myth of Sisyphus, in which he elevates Sisyphus to the status of absurd hero.

- Franz Kafka repeatedly referred to Sisyphus as a bachelor; Kafkaesque for him were those qualities that brought out the Sisyphus-like qualities in himself. According to Frederick Karl: "The man who struggled to reach the heights only to be thrown down to the depths embodied all of Kafka's aspirations; and he remained himself, alone, solitary."[28]

- The philosopher Richard Taylor uses the myth of Sisyphus as a representation of a life made meaningless because it consists of bare repetition.[29]

- Wolfgang Mieder has collected cartoons that build on the image of Sisyphus, many of them editorial cartoons.[30]

See also

- The Myth of Sisyphus, a 1942 philosophical essay by Albert Camus which uses Sisyphus's punishment as a symbol for the absurd.

- Sisyphus: The Myth, a 2021 South Korean TV series, which uses the myth as a symbol for its theme.

- Sisyphus cooling, a cooling technique named after the Sisyphus myth

- Syzyfowe prace, a novel by Stefan Żeromski

- Comparable characters:

- Naranath Bhranthan, a willing boulder pusher in Indian folklore

- Jan Tregeagle, a Cornish magistrate who must empty Dozmary Pool with a limpet shell or weave sand into rope at Gwenor Cove

- Tantalus, who was similarly punished with a neverending toil

- Wu Gang – also tasked with the impossible: to fell a self-regenerating tree on the Moon

Notes

- ^ museum inv. 1494

- ^ "Sisyphean". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. xxxiii.

- ^ Gruppe, O. Griechische Mythologie (1906), ii., p. 1021

- ^ Apollodorus, 1.7.3 Archived 8 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Scholia on Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica 3.1094

- ^ Pausanias, 2.4.3 Archived 13 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d Apollodorus, 1.9.3 Archived 2 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Homer, Iliad 6.152 ff.

- ^ Scholia on Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica 3.1553

- ^ Scholia on Homer, Iliad 2.511

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae 201; Plutarch, Quaestiones Graecae 43; Suida, s.v. Sisyphus Archived 25 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Morford & Lenardon 1999, p. 491.

- ^ "Ancient Greeks: Is death necessary and can death actually harm us?". Mlahanas.de. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ "Encyclopedia of Greek Mythology: Sisyphus". mythweb.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ "Sisyphus". www.greekmythology.com. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Evslin 2006, p. 209-210.

- ^ "Homeros, Odyssey, 11.13". Perseus Digital Library. Archived from the original on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ a b Homer, Odyssey 11.593

- ^ Pausanias, 10.31

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 161.

- ^ De Rerum Natura III

- ^ Revue archéologique, 1904

- ^ Sansonese, J. Nigro. The Body of Myth. Rochester, 1994, pp. 45–52. ISBN 0-89281-409-8

- ^ Ariely, Dan (2010). The Upside of Irrationality. ISBN 978-0-06-199503-3.

- ^ Ovid. Metamorphoses, 10.44.

- ^ Apology, 41c

- ^ Karl, Frederick. Franz Kafka: Representative Man. New York: International Publishing Corporation, 1991. p. 2

- ^ Taylor, Richard. "Time and Life's Meaning." Review of Metaphysics 40 (June 1987): 675–686.

- ^ Wolfgang Mieder. 2013. Neues von Sisyphus: Sprichtwortliche Mythen der Antike in moderner Literatur, Medien und Karikaturen. Vienna: Praesens.

References

- Evslin, Bernard (2006). Gods, Demigods and Demons: A Handbook of Greek Mythology. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-84511-321-6. Archived from the original on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- Homer, The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PhD in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library. Archived 6 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Homer. Homeri Opera in five volumes. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 1920. Greek text available at the Perseus Digital Library Archived 18 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine.

- Homer, The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library. Archived 8 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine Greek text available from the same website Archived 8 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine.

- Morford, Mark P. O.; Lenardon, Robert J. (1999). Classical Mythology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514338-6. Archived from the original on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- Pausanias, Description of Greece with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, M.A., in 4 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1918. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library Archived 5 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Pausanias, Graeciae Descriptio. 3 vols. Leipzig, Teubner. 1903. Greek text available at the Perseus Digital Library Archived 31 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine.

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, The Library with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library. Archived 28 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine Greek text available from the same website Archived 10 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine.

- Publius Ovidius Naso, Metamorphoses translated by Brookes More (1859–1942). Boston, Cornhill Publishing Co. 1922. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library. Archived 6 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Publius Ovidius Naso, Metamorphoses. Hugo Magnus. Gotha (Germany). Friedr. Andr. Perthes. 1892. Latin text available at the Perseus Digital Library Archived 6 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.